Are you customer-focused or customer-centric?

You may be aware the Australian Podiatry Association (APodA) is currently undergoing an exciting period of development marked by the appointment of Chief Executive Officer, Hilary Shelton. As the APodA strengthens its ongoing journey in customer-centricity, some recent insights are shared below for broader understanding.

The upcoming release of the APodA Strategic Plan for 2025 to 2027 enables the APodA to reflect on how it operates and why it exists; to reassess its purpose and values against emerging strategic pillars.

Strengthening customer-centricity

Driving this shift is a deliberate move towards becoming increasingly customer-centric. This demands the APodA to become bolder and think even bigger; to embrace untapped opportunities. The upcoming strategic plan is embedded in this commitment to customer centricity; given our purpose can only be fully nurtured through this approach.

To explore the difference between being customer-focused and customer-centric, we need to first transverse through some subtle nuances and learn together. The following insights have given the APodA cause to reflect, and they are shared below for widespread benefit.

Universal lessons for everyone

#1 What is your why?

As the APodA team collaboratively explores new ways of working, facilitated by transformation consultancy nue21, emerging lessons hold universal relevance. In fact, one of its starting points may be something you too, wish to ask yourself: why does your role or business exist?

Chances are, the answer you immediately provide may not go as far as your potential could reach. Try to think bigger if you can, even to the point of discomfort. What is the biggest conceivable purpose that captures why you get out of bed every day, to strive for what it is that you do?

#2 Who are your customers?

This line of thinking may bring up deeper reflections on who your customers are. As a podiatrist your customers are your patients; but they may also include your local community, key suppliers, or sporting groups. The APodA is also in the process of defining our customers, with members remaining at the heart of such considerations.

#3 Where do you stand (and where do you want to stand?)

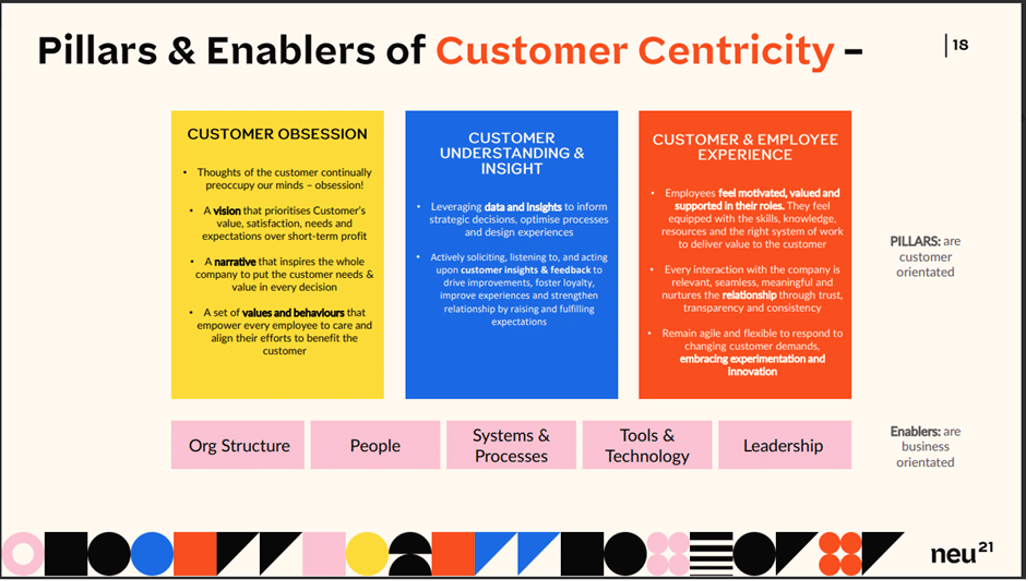

Next, reflect on whether your ‘modus operandi’ is customer-focused or customer-centric; bearing in mind being customer-focused is no easy feat in itself. Is there scope to go even further with the service you provide, particularly in pursuit of a revised purpose? Again, try to sit within any discomfort if you can, since discomfort can be the precursor to progress.

The accompanying visuals crafted by nue21 may help to gauge where you currently stand on the spectrum of customer focus versus customer centricity.

Where the APodA is at

As the APodA continues on this path, marked by the strategy’s release in the coming months, it will continue to share insights on what it means to be customer-centric. Like any transformation, this path will not be linear or perfect. Mistakes will be made and an intrinsic part of this process is accepting that the path to customer centricity is never fully realised. It is deliberately ongoing, requiring constant reflection and improvement.

Whatever lessons lie ahead for the APodA, it will continue to embrace any such discomfort in support of greater growth; for everyone’s sake and most of all – for the sake of the profession and the health consumers it serves.

AD

A proud STRIDE advertiser

How to expand your online visibility

Marketing manager, Lachlan Hetherington, shares tips on how to expand your footprint and become the go-to provider in your area.

Imagine if I told you that you could place a billboard for your practice right in front of thousands of people in your local community who are looking for a podiatrist? In addition to having all-important visibility on Find a Podiatrist, there are other ways to be found online.

In fact, a strong online presence can transform your local podiatry practice into being the go-to provider in your local area. Ready to learn how? Let’s dive into some of the strategies.

Do you have a glorified business card?

It’s alarming how many practices are missing out on potential bookings due to poor website layout. With 98 per cent of websites resembling glorified business cards; what do I mean? They typically feature the business name, contact information, a long list of services, and an ‘About Us’ section.

Sound familiar? How do we turn it into an attractive appointment booking machine?

We have two main objectives: First, build a site that prompts clients to pick up the phone or book an appointment, acting like a 24/7 receptionist. Second, optimise the website to please the Google machine. More on that later.

If you want your website to work much harder for you, beyond being a glorified business card, then bear the following tips in mind.

1. Build an appointment-making machine

- Speak directly to your ideal clients: If you want to attract athletes to your practice. Talk directly to them, call them out. If you want more custom orthotics clients, position yourself as the go-to custom orthotics distributor and know precisely why your orthotics are better than others. Remember, the generalist never wins.

- Highlight your difference: Highlight the points where your service is different, or specific areas you focus on.

- Create a clear ‘call to action’: A confused client never books. Don’t leave your visitors guessing. Use strong calls to action like ‘Book Now’ or ‘Call Today’ in prominent positions on your website.

2. Nurture the Google machine

- Check your mobile-first optimisation: Have you ever looked at your website on a mobile device? With over 70 per cent of web traffic coming from mobile devices, your site must look great and load quickly on smartphones.

- Revisit your local strategy: Use relevant local keywords on your website that potential clients will use to find a podiatrist in your area. Examples include ‘Ingrown Toenail Treatment Melbourne’, ‘Custom Orthotics Brisbane’, or ‘Sydney Podiatrist’.

- Build local links: Think of links from other websites to yours as votes of confidence. The more reputable sites that link to you, the more credible your practice appears to Google. The more you will climb in rankings.

- Build relationships with your local community: Reach out to local health blogs or community websites, and offer to write guest posts or share insights. A link back to your site from theirs boosts your credibility.

- Collaborate with local businesses: Partner with local healthcare providers. For example, a physiotherapist could recommend your podiatry services on their site, and you could do the same for them. This mutual support enhances both of your online presences.

- Keep your Google ‘My Business Profile’ active: Regularly update your profile with new photos, service updates, and posts about special events or promotions. Businesses with complete listings are twice as likely to be considered reputable by consumers.

- Respect the business listing: Imagine driving to a new restaurant only to find the address listed online was wrong. Frustrating, right? Consistency in your business listing information is crucial.

3. Value the importance of reviews

- Build trust: What does a client have to feel before booking an appointment? Trust. Google reviews build trust and your new clients will read your online reviews before booking an appointment. The more positive reviews you have, the more likely they are to choose you. According to a study, 91 per cent of consumers read online reviews, and 84 per cent trust them as much as personal recommendations. I am sure you have read the reviews when seeking a new service, before trying a new restaurant or seeking more information on a product.

- Ask your clients: Asking your clients to see if they would be interested in leaving you a Google review. Please note you are not able to advertise reviews that refer to any treatment.

- Engage with reviews: Most practices forget to respond to the reviews. Yet responding shows you care about your client’s feedback. Thank those who leave positive comments and address any negative reviews professionally, and with respect.

- Read the guidelines: The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) has guidelines to help podiatrists understand what they can and can’t do.

4. Remember that content is (still) king

- See your website as an informative resource: Imagine your website as a treasure trove of valuable information. Regularly updating it with informative, engaging content keeps visitors coming back.

- Create original, valuable content: Focus on well-researched articles that address common questions and concerns of your patients. For instance, write about, ‘How to prevent ingrown toenails’ or ‘Choosing the right running shoes’. Businesses that blog receive 55 per cent more website visitors than those that don’t.

- Use different media: Incorporate videos and infographics. These varied content types cater to different preferences and can be more engaging than text alone.

The biggest takeaway

By optimising your website, gathering positive reviews, building strong network links, maintaining consistent business listings, and creating high-quality content, your podiatry practice can significantly enhance its online presence.

These steps will help you to become the preferred choice for podiatry services in your area, driving growth and establishing your practice as a trusted provider. Start implementing these strategies today and watch your patient-base expand as more people discover and choose your exceptional services.

Business resources guide for podiatrists

Running a successful podiatry practice in Australia involves more than just providing excellent patient care. It requires effective business management, compliance with regulations, and keeping updated on industry standards.

Here’s a detailed guide that lists essential resources available, with useful links and explanations of their benefits.

First up…the Australian Podiatry Association

Members of the Australian Podiatry Association will already be aware of the resources and support available to them as podiatrists – and as business owners, whether sole traders or company owners.

From the Member Assistance Program, clinical resources, advocacy representation, human resources support, insurance cover and advice, through to Journal Club, Special Interest Groups, member-only social media forums, classified listings, legal insights, CPD, Career Framework pathways, webinars, events, patient resources, and online tools. The APodA has plenty of resources, specifically for podiatrists, alongside real-time advice when you most need it.

Next … some additional resources

1. Business.gov.au

How it can help you: Business.gov.au is a comprehensive portal designed to support business management and regulatory compliance. It offers tools and templates to help with business planning, financial management, and understanding legal obligations. This is especially useful for new practice owners or those looking to optimise current operations.

Key features:

- Business Plan templates

- Marketing Plan templates

- Succession Plan templates

- Sustainability Action Plan templates

- Compliance Guides

- Financial Management Tools

2. Australian Taxation Office (ATO)

How it can help you: The ATO provides essential information on tax responsibilities, deductions, and financial management. This helps podiatrists navigate GST, income tax, and other financial matters, ensuring compliance and optimizing financial practices.

Key features:

- Tax Basics: Guides on GST, PAYG, and other tax responsibilities.

- Deductions and claims: Information on what expenses can be claimed.

- Financial tools: Includes calculators for budgeting and tax.

3. Podiatry Board of Australia

How it can help you: Supported by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) in each state and territory, the Podiatry Board of Australia has established a Registration and Notification Committee to make decisions about registration and notifications matters where the Board has delegated powers under the National Law.

In addition to setting the Code of Conduct, the Podiatry Board of Australia (PBA) registers podiatrists and students; develops standards, codes and guidelines for the podiatry profession; handles notifications, complaints, investigations and disciplinary hearings; assesses overseas trained practitioners who wish to practice in Australia and approves accreditation standards and accredited courses of study.

Key features

- Code of Conduct: Download the Code on professional behaviour and ethical standards.

- Apply for registration and endorsement

- Renew your registration

4. Small Business Ombudsman

How it can help you: The Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman (ASBFEO) provides free assistance and advice on small business issues, including disputes, regulatory compliance, and navigating government processes. This resource helps podiatrists manage challenges and ensure smooth practice operations.

Key features:

- Dispute resolution: Assistance with resolving business disputes.

- Regulatory guidance: Interpretation of complex regulations.

- Business support: General advice on managing and growing your practice.

5. My Business Health

How it can help you: My Business Health offers tailored advice and resources for small business owners, including health practitioners. It provides insights into business planning, financial management, and resilience.

Key features:

- Business planning resources: Assistance with creating and refining your business strategy.

- Financial management tools: Budgeting and cash flow resources.

- Resilience tips: Guidance on managing business challenges.

6. Australian Business Grants

How it can help you: Grants and funding opportunities can provide financial support for expanding your practice, investing in new technology, or conducting research. This portal lists available grants, eligibility criteria, and application processes, helping podiatrists secure necessary funds for growth and innovation.

Key features:

- Grant listings: Current information on available grants.

- Eligibility guidelines: Helps determine if you qualify for various grants.

- Application advice: Tips for preparing grant applications.

7. Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC)

How it can help you: As health data becomes increasingly digital, protecting it from cyber threats is crucial. The ACSC provides resources and guidelines to help secure your practice’s digital assets, ensuring compliance with data protection regulations.

Key features:

- Cybersecurity guidelines: Best practices for securing your practice.

- Threat intelligence: Updates on emerging cyber threats.

- Security tools: Free tools and resources for enhancing cybersecurity.

8. HealthDirect

How it can help you: HealthDirect provides a range of health information resources for both practitioners and patients. For podiatrists, it offers clinical guidelines, patient education materials, and updates on health conditions and treatments, ensuring evidence-based care.

Key features:

- Clinical guidelines: Latest guidelines and best practices.

- Patient resources: Information to support patient education.

- Small Business Ombudsman: News on emerging health issues and research.

What the research tells us: Achilles tendinopathy

Podiatrist Blake Withers shares the following piece of research for the benefit of podiatrists; reflecting on why the research is relevant, and how to implement it.

What study are we looking into this month?

Are we asking the right questions to people with Achilles tendinopathy? The best questions to distinguish mild versus severe disability to improve your clinical management.

Who are the authors/researchers?

- Myles C. Murphy

- Brady Green

- Igor Sancho Amundarain

- Robert-Jan de Vos

- Ebonie K. Rio

What is the goal behind the research?

To determine which questions from the Achilles TENDINS-A, Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS), and Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment (VISA-A) are best able to distinguish mild and severe disability in patients with Achilles tendinopathy (1, 2, 3).

What are your thoughts on this research?

These outcome measures are consistently used in research, but not as much in clinical practice. There are great questions within these measures, but they can be time-consuming, often forgotten, and may not seem relevant to the patient. They each have their advantages and disadvantages.

However, they provide an objective outcome in the subjective world of pain and function. If you are not familiar with them, I have provided a brief explanation and some example questions below.

- The FAOS is a patient-reported foot-and ankle-specific questionnaire including 42 items in evaluating pain, symptoms, function of daily living (ADL), function in sport and recreation and quality of life (3).

- The VISA-A is a valid and reliable index of the clinical severity of Achilles tendinopathy (4). For instance, in the VISA-A, two sample questions are:

Rating on a scale from 0 to 10

Do you have pain walking downstairs with a normal gait cycle?

Strong severe pain 0 to No pain 10

Or

Do you have pain during or immediately after doing 10 (single leg) heel raises from a flat surface?

Strong severe pain 0 to No pain 10

Do you use this approach yourself?

Personally, I don’t use these outcome measures often, but I use my own framing of questions from each to incorporate into my assessment.

I believe it’s important to enquire about pain during meaningful activities and also to enquire about pain over a 24-hour period. These are the aspects people most frequently mention when describing their symptoms.

In the context of this study, we know that tendon pain is limiting for people who want to do more of what they enjoy. Qualitative studies echo this frustration, reporting patient comments such as, “I think it restricts me in a lot of things that I would be able to do”. Or, “You want it to happen now. You’re doing all this stuff and it’s just very slow progress.” (5)

It’s clear that people want to get back to their meaningful activity with manageable pain levels; whether it be karate, running, or walking with friends. Tendinopathy requires an individualised approach to management. These questionnaires, in combination with our advice can help that.

What do you feel is of particular interest to podiatrists regarding this research?

Several points come to mind.

- We can use these measures to assess improvement and tailor our advice. It is worth checking these measures out; they may work well in some cases and have been validated.

- We know Achilles tendinopathy (AT) can persist for a long time (2, 5, 6). One-fifth of patients with conservatively treated midportion AT still have symptoms after 10 years (2). Symptoms can vary, and quality of life can be reduced because of it (2, 5). It is like plantar heel pain, meaning a lot of our advice revolves around prognosis and helping people understand that although slow progress can be frustrating, it is still progress.

- For podiatrists, understanding the severity of a condition and its potential prognosis helps us better inform our patients with education and advice. Although we know that low and stable symptoms are a good sign in tendinopathy, it can be difficult for someone who has had pain for eight months to accept.

Why is this of particular interest to you, to share with fellow podiatrists?

In healthcare, we all want to understand what the ‘special’ test is: the assessment, image, or questions that will give us all the answers. As we know, there isn’t one.

Orthopaedic tests vary in their sensitivity and specificity but they can help form a diagnostic and treatment framework (7). When it comes to Achilles tendinopathy, some questions can really help us as podiatrists:

- Ask if someone experiences night pain, as it might help in the diagnosis of a bone stress injury.

- Ask if someone has pain with high rates of loading, as it might help to rule out a peritendon (and rule in a tendinopathy).

Imagine if we had some questions to help differentiate between severe and mild Achilles tendinopathy? Questions that could give us more confidence in providing quality advice to patients?

For example, if over a two-month period someone reports their morning pain hasn’t changed at all, but they’re back to running 20 km from 0 km per day, and their pain subsides within 24 hours, then that’s a significant improvement. We may use that evidence to inform our education, which is a large part of what we do.

In our role, we function somewhat like guides, to assist individuals on their journey back to their desired outcomes. It involves various forms of support, with a significant part being the reassurance of staying on track despite encountering troublesome but manageable problems. This becomes all the more pronounced when various modalities have been implemented and there is more time between appointments.

The typical approach for managing an Achilles tendon issue involves staying consistent with rehab, engaging in meaningful activities, managing flare-ups, and allowing time for recovery. We need the confidence to inform our education when explaining that these current symptoms are typical and manageable, and that they do not indicate a need for significant changes.

Now you might be thinking, ‘If I had a dollar for every time you said education, I could probably retire’, and you’d be right. Patients with pain want clarity and understanding. I believe most people with persistent pain don’t expect their pain to go away quickly, but being more confident in our understanding of what constitutes improvement is helpful.

Were there any other areas within this research that you found interesting?

Definitely. Several questions were found in the research to be poor indicators of severity. These included whether patients have Achilles tendon stiffness, pain at rest, or pain during activities of daily living.

Patients often ask about these symptoms, since they are a common frustration.

If we know these areas are a poor indicator of severity, it doesn’t mean we say, ‘That doesn’t matter’, but it does mean we can be confident in using other metrics to gauge recovery, and thus education.

How can podiatrists use this new knowledge immediately?

Action points from this study share some very useful questions to aid podiatrists in forming a clinical picture. We can use the below questions in our initial assessment and during follow-up, to aid in our understanding of the severity. This can, in turn, help with our education.

Here are the questions that the authors concluded as being important to ask:

- The top ten best-performing items are:

- Numerical rating scale of pain with single-leg hopping.

- Numerical rating scale of pain with double-leg jumping.

- How many single-leg hops can be completed without pain?

- Time taken for pain to subside following aggravating activities (minutes).

- Numerical rating scale of pain with a single-leg calf raise.

- Numerical rating scale of pain with a double-leg calf raise.

- Time taken for stiffness/symptoms to subside following waking (minutes).

- Time taken for stiffness/symptoms to subside following prolonged sitting (minutes).

- Degree of reduction in physical activity from pre-injury levels.

- Difficulty in completing running in the past week.

If a podiatrist wants to discuss this with you, how can they contact you?

Instagram – @BlakeWithers.Sportspodiatrist

Podcast: Sports Medicine Project

References:

- Murphy MC, Newsham-West R, Cook J, Chimenti RL, de Vos RJ, Maffulli N, et al. TENDINopathy Severity Assessment – Achilles (TENDINS-A): Development and Content Validity Assessment of a New Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Achilles Tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2023;54(1):1-16.

- Lagas IF, Tol JL, Weir A, de Jonge S, van Veldhoven PLJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. One fifth of patients with Achilles tendinopathy have symptoms after 10 years: A prospective cohort study. J Sports Sci. 2022;40(22):2475-83.

- Larsen P, Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Elsoe R. Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS): Reference Values From a National Representative Sample. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2023;8(4):24730114231213369.

- Robinson JM, Cook JL, Purdam C, Visentini PJ, Ross J, Maffulli N, et al. The VISA-A questionnaire: a valid and reliable index of the clinical severity of Achilles tendinopathy. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2001;35(5):335-41.

- Turner J, Malliaras P, Goulis J, Mc Auliffe S. “It’s disappointing and it’s pretty frustrating, because it feels like it’s something that will never go away.” A qualitative study exploring individuals’ beliefs and experiences of Achilles tendinopathy. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233459.

- von Rickenbach KJ, Borgstrom H, Tenforde A, Borg-Stein J, McInnis KC. Achilles Tendinopathy: Evaluation, Rehabilitation, and Prevention. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2021;20(6):327-34.

- Rubinstein SM, van Tulder M. A best-evidence review of diagnostic procedures for neck and low-back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(3):471-82.

Upholding the significance of professional identity

President of the Australasian College of Podiatric Surgeons and podiatric surgeon, Angelo Salerno, reflects on the ‘Independent review of the regulation of podiatric surgeons in Australia’.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and are not intended to reflect the views of the Australian Podiatry Association, or other entities external to the Australasian College of Podiatric Surgeons.

What was the independent review about?

A review was established to examine the existing regulation and regulatory practices used by the Podiatry Board of Australia and the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra). The Independent review of the regulation of podiatric surgeons in Australia aims to ensure the appropriate standards, guidance and processes are in place to support safe practice by podiatric surgeons in Australia; and to make recommendations for any necessary changes.

How does the review impact podiatric surgeons?

The review has provided an opportunity to deeply reflect on current practices, to identify areas of improvement, and to collectively work together to further enhance the quality of care and safety for practitioners and patients.

How is the ACPS responding to the review?

The Australian College of Podiatric Surgeons (ACPS) is actively engaged in addressing the recommendations made by the independent review.

The independent review identifies consumer confusion surrounding the use of the titles ‘podiatric surgeon’, ‘surgeon’, and ‘doctor’ and it recommends a title change. This recommendation presents a distinct issue for the ACPS.

We are taking steps, through a newly-formed working party, to address the areas identified as requiring improvement. The ACPS position statement can be found on the ACPS website.

How do members of the ACPS feel about the recommendation for a title change?

It is a contentious matter that evokes strong emotions and is a major concern for members of the ACPS. Our argument for the retention of the title ‘surgeon’ relates to the fact that we are a sub-speciality of the podiatry profession that has completed adequate training and is regulated to perform specific types of surgery.

I believe any such decision should address the interplay between tradition, public perception, the issue of specialisation and scope of practice, international precedents, and professional equality and regulatory frameworks.

Historically, the distinction between surgeons and physicians was quite pronounced.

Surgery was viewed as a separate practical craft, rather than part of formal medical education. Surgeons were frequently craftspeople who learned through apprenticeship and hands-on experience, distinct from physicians who focused on medical theory and prescribing treatments. During the Renaissance, surgeons increasingly acquired their skills through formal training, though apprenticeship remained important.

For more historical context, Lewis Durlacher (1792-1864) was a notable figure in the field of chiropody, which is now more commonly known as podiatry. Durlacher was appointed as the surgeon-chiropodist to Queen Victoria. His surgical techniques helped to set the stage for modern podiatric surgery.

Regarding the public’s perception and clarity around the title ‘podiatric surgeon’, how is that a point for consideration?

The title ‘surgeon’ holds significant public recognition and clarity, conveying a clear understanding that the individual is qualified to perform surgical procedures.

This public recognition is crucial to establish trust and confidence among patients, particularly in fields where surgery is a central aspect of practice.

The term ‘surgeon’ has become synonymous with several factors: the public’s perception of specialised training, expertise in surgical techniques, and the ability to perform procedures safely and effectively. It sets a clear expectation that the practitioner has undergone rigorous education and training, specifically focused on surgical interventions.

This clarity fosters trust in healthcare providers and facilitates informed decision-making when seeking surgical treatment. Changing the title could undermine this expectation and lead to confusion around the expertise and training required to perform surgical procedures competently. Podiatric surgeon is the most accurate and succinct title, particularly given the specialist training and level of qualification required; and as a title that most accurately describes the activity itself, being surgery.

Reducing the title could lead patients to underestimate the complexity and seriousness of the surgeries performed, potentially resulting in inadequate postoperative or follow-up care.

Do you believe the answer is straightforward; to keep the title of ‘podiatric surgeon’ without making further adjustments?

Yes. We firmly believe there is no necessity for a change in title if regulators and the podiatry profession, including the ACPS, provide clarity and transparency in educating healthcare consumers about our role.

We recognise the potential for public confusion regarding the title ‘podiatric surgeon’. Terms like ‘surgeon’ and ‘doctor’ may imply that we are medical practitioners who have attended medical school. It is crucial to clarify that while we perform surgical procedures, we are not medical doctors. We are committed to ensure clarity and transparency around this issue, to avoid any misunderstanding among the public.

If podiatric surgeons provide full disclosure to patients as part of the consenting process, to explain our qualifications and scope of practice, this can mitigate any potential confusion.

Such disclosure can be reinforced through informative resources, provided by podiatric surgeons and referring practitioners. If we inform the public better than we have done in the past, we can address the issue of public confusion; negating the need for a title change.

Can you provide an example as to how this might work in practice?

Certainly. As an example, before a patient visits a podiatric surgeon, it is important for the referring practitioner to provide them with informative brochures that outline the identity and scope of our services. Such resources are provided by the ACPS and they will have a pivotal role in empowering patients to aid informed decision-making.

The podiatric surgeon then supplements this information with additional details, shared during the consultation, to ensure patients are well-informed and confident in their choices.

Importantly, in this example, the podiatric surgeon would provide full disclosure to patients, so this information-sharing becomes part of the consenting process. Ultimately, the patient would read, understand and sign off on this information before they have treatment with a podiatric surgeon.

For example, the disclosure could be along the lines of:

I understand that a podiatric surgeon is a registered specialist podiatrist who is trained in the diagnosis and treatment of foot and ankle disorders by both surgical and non-surgical methods and is not a medical practitioner (medical doctor).

What are your thoughts on the title of ‘podiatric surgeon’ in the context of the regulatory framework and standards?

The title ‘surgeon’ is underpinned by a rigorous regulatory framework and standards, to ensure professionals are fully equipped to perform surgeries safely and effectively.

The process of becoming a surgeon involves extensive education and training. These programs are designed to provide in-depth knowledge of surgical techniques, anatomy, and patient care; as well as hands-on experience in performing surgeries under the supervision of experienced surgeons.

The documented regulation, compliance and oversight provided by Ahpra, PBA and the ACPS, ensures that anyone bearing the title ‘surgeon’ adheres to high standards of education, training, and ethical practice.

This not only guarantees the competence of surgeons but ensures public safety and trust in the healthcare system. Patients can be confident that podiatric surgeons have been thoroughly vetted, and are qualified to provide the highest standard of care.

How does the issue of specialisation and scope of practice come into consideration, when you reflect on a potential title change?

Specialisation and scope of practice are critical aspects of the title ‘surgeon’, particularly for occupational groups who are trained to perform specific types of surgeries.

- Firstly, these groups may not require full medical training, but they need a high level of specialised skill and knowledge to carry out their surgical duties effectively and safely. In many medical fields, specialisation allows practitioners to focus on particular areas of surgery, to develop deep expertise and proficiency in specific procedures. For instance, orthopaedic surgeons, cardiovascular surgeons, and neurosurgeons all undergo specialised training tailored to their particular surgical domains. Similarly, other surgical professionals, such as podiatric surgeons or dental surgeons, receive focused training that equips them to perform surgeries within their specialised fields.

- Secondly, the use of the title ‘surgeon’ acknowledges this specialised element of their practice. This title distinguishes these professionals from generalist practitioners, and highlights expertise in their particular surgical domain. This distinction is essential for patient understanding, to provide clarity around the specific skills and qualifications that the surgeon possesses. The title ‘surgeon’ thus becomes an indicator for specialised training and expertise; signifying that the individual is qualified to carry out the surgical procedures pertinent to their field.

- In Australia, oral surgeons are licensed to perform oral surgery. Their training involves extensive education in dental schools, followed by specialised surgical training. Similarly, podiatric surgeons undergo rigorous training focused on surgical procedures related to the foot and ankle. These professionals are recognised as surgeons, due to their specialised knowledge and skills; despite not having a traditional medical degree.

- Thirdly, the term ‘podiatric’ originates from the Greek word ‘podos’, which pertains to the foot. This establishes the title within the field of podiatry, being a specialised area of healthcare that focusses on diagnosing, treating, and preventing conditions that affect the feet and ankles. By including ‘podiatric’ in the title, a distinct boundary is defined, marking it as separate from other healthcare professions and differentiating it from other medical fields.

- Finally, the title ‘podiatric surgeon’ is not just a semantic choice, but an accurate designation that encapsulates the specialised nature of those it represents. This title, when examined, reveals a deliberate and precise choice of words that aligns with the unique expertise and skills possessed by this profession. Hence, ’podiatric surgeon’ is suitable given the straightforward linguistic notion that a surgeon is an individual who performs surgery.

One might argue that the alternative term, ‘surgical podiatrist,’ is also linguistically valid, yet it is not consistent with other similar terminologies. For instance, we refer to dental surgeons, not surgical dentists.

Additionally, this term is not commonly used by the professional bodies or the training institutions that represent these practitioners, and hence, it does not effectively fulfill its descriptive function. I believe this perspective is consistent with the argument presented in a paper titled ‘Foot’ and ‘surgeon’: a tale of two definitions (2010), where it critiques the concept of ‘surgical podiatrist’ as flawed in differentiation from ‘podiatric surgeon’. The publication continues to explain the adjective, ‘surgical’, can be defined as ‘relating to or used in surgery’, which infers that the podiatrist is performing surgery, and the noun for someone who performs surgery is, of course, ‘surgeon.’

Are there international precedents in place (which reflect also on professional equality?)

Yes. International precedents highlight the use of the title ‘surgeon’ by professionals with specialised surgical training who may not possess a traditional medical degree.

For instance, dental surgeons (dentists) and podiatric surgeons are recognised as surgeons within their specific scopes of practice across many countries. These professions exemplify how specialised training equips individuals to perform surgical procedures effectively, warranting the title “surgeon.”

It is important to continue to align with our international peers, such as in the UK, where terms such as ‘consultant podiatric surgeon’ and ‘podiatric surgeon’ are recognised and have been used within the National Health Service (NHS) for many years reflecting the roles podiatric surgeons fulfill. Likewise, the term ‘podiatric surgeon’ has been in use in the USA for decades.

Any final thoughts to share?

The protected title, ‘podiatric surgeon’ is appropriately used by podiatric surgeons under the National Law and has been accurately informing the Australian public for more than 10 years. All available evidence supports the facts that podiatric surgery is safe, effective and costs the public less than other providers of the same service.

The Travelling Pod | Part 4 | Turning bottle caps into orthotics

David Karamanis, aka ‘The Travelling Pod’ created customised orthotics from plastic Coke bottle caps, which was explored in last month’s issue of STRIDE. This month he shares another experience where he made an orthotic out of bottle caps and tracked its longer-term efficacy.

David works with travelling migrants who temporarily live beside a train station in Mexico. These people may not otherwise be able to access podiatric intervention and related resources.

Follow David’s adventures and watch videos of his daily interactions at The Travelling Pod on YouTube.

I have been providing podiatry service for the passing migrants since April 2023, and despite the limitations of my environment and resources, my level of service has been getting better. I am learning how to maximise the little resources that I have by using old unused thongs/flip flops and making semi-customised orthotics (using the recycled thongs method). Unable to measure its effectiveness due to the lack of feedback, I have been able to use my girlfriend’s foot pain as a ‘case study’.

What I have learned

I have been able to measure the effectiveness of the ‘recycled thongs method’ to be effective up until three months, at which point, it loses its supportive properties.

For more context, my girlfriend has always had chronic medial sesamoiditis for years, which was problematic after long walks. In March 2024 we went to Guatemala and hiked four volcanoes with the highest point of 4000 meters above sea level. Two weeks before leaving for our vacation, using the recycled thongs method, her orthotics were effective in reducing her foot pain completely using the same pair of shoes. However, after three months her pain returned with signs of planter fasciitis around the medial longitudinal arch (MLA).

The process

I have always wanted to create a customised orthotic using plastic similar to what I was doing in a private clinic in Australia. This was not without limitations, I was not able to use a scanner, computer CAD program, or 3D printer. Therefore, I was to use the old-school method of using plaster to make a positive cast and using polypropylene plastic to mold an orthotic. However, I had to make a cost-effective orthotic within a couple of hours. That meant that I had to modify the steps of orthotic design that I had learned at university.

The challenges

The first problem to tackle was casting: do I cast weight-bearing or non-weight-bearing? Previously in Australia, I scanned the foot holding it in a position that I thought was appropriate and non-weight bearing. Therefore, with intrinsic modifications, I did not have to externally modify much using the CAD computer program when designing the orthotics. However, the situation in Mexico was different, and to save time I decided to cast weight bearing.

Advice along the way

I got some much-needed advice from my orthotics teacher Derick at Western Sydney University about how to cast weight bearing, and he suggested using sand. Absolute genius, I had not thought of that. However, my first attempt was a massive failure because the sand in the box was uneven and influenced my cast in the sagittal plane.

Therefore, I used a flat piece of wood and surrounded the unilateral foot whilst the person held onto a chair for stability. This meant that the weight-bearing foot was under a lot of load, I dorsi-flexed the big toe to activate the windlass mechanism, then slightly supinated the rearfoot. Furthermore, once in this altered foot position, I added more sand to form this new position, then the person removed their foot slowly. I was able to get their current shoe innersole and mold the forefoot to the exact shape for fitting purposes. Then, I added plaster to make the shape and did the same process for the other foot. Once the plaster was set, I smoothed the harsh edges with more plaster.

Trial and error

I thought finding polypropene 3mm sheets would be easy, recycling unwanted offcuts or even purchasing. Nothing was easily available so I continued the thought of recycling my own plastic to use.

Last year, I had this idea and tried to melt HDPE 2 plastic that I had collected and cut, arranged in different densities. I researched that 180 degrees was safe and appropriate to melt plastic, as demonstrated on YouTube. This was a massive disaster. After nearly an hour it had not melted so I turned the oven heat up and the plastic started to burn and release dangerous toxins. Then, when removing the glass baking tray from the oven, it exploded near my face, without any injuries. I was discouraged in recycling plastic.

A promising method

Since I could not find polypropylene plastic, I decided to return to my journey into recycling plastic but found another video that demonstrated melting plastic from bottle caps. I collected over 200 Coke plastic bottle caps for this project, bought a flat sandwich press, and heat appropriate material to melt the bottle caps. After a few failed attempts, I created an even-density rectangle shape of 4mm plastic that I transferred onto my positive cast.

The plastic was fine to work with, but needing to do everything quickly whilst it was hot, I molded the heel cup and MLA as priorities. I used my heat gun to alter the edges until I was satisfied with the shape. I used my Dremel to cut off excess plastic and shape the orthotic. Lastly, I glued a 2mm medium-density material on the posterior side, and a 5mm EVA-like material as a top cover to make a full-length orthotic.

One month after using her new orthotics, her feedback has been encouraging. She has never had anything more comfortable; she continues to wear and exercise in her custom orthotics. Also, her symptoms have significantly reduced since the first week of wearing them.

This entire process has been filmed and is captured in this Part 1 video and this Part 2 video.

A case for sustainability

This opens the conversation for sustainability in podiatry, and I have videos about this on my YouTube. Are there opportunities for an eco-friendly customised orthotic using the recycled bottle cap technique? I would be interested in hearing your thoughts.

Get in touch

Follow The Travelling Pod

YouTube: The Travelling Pod

Instagram: www.instagram.com/the_traveling_pod/

Website: www.TheTravelingPod.com

When does an examination turn inappropriate?

This article is facilitated by APodA’s insurance partner BMS, and written by health law firm Barry Nilsson.

As a podiatrist, you are required to touch, manoeuvre and manipulate patients’ limbs and body parts, which involves close physical contact. While what could be conceived as inappropriate touching may seem obvious, even the most experienced podiatrists may unintentionally find themselves in a challenging situation.

Scott Shelly and Daryl Langman of health law firm Barry Nilsson, illustrate how routine assessments can sometimes turn inappropriate.

Special HR report | Part 1 | Do you know the latest on remote work rules?

In this two-part special HR report, the ever-changing role of remote work and flexible work arrangements is examined to see where the law lands when it comes to an employer’s responsibility and an employee’s obligations.

In recent years – namely the Covid-19 era – the workplace landscape has undergone a significant transformation, with remote working emerging as a defining feature of modern employment in many industries. However, it’s important to recognise that remote work is not feasible for all industries or roles. For many businesses, particularly those requiring a physical presence, alternative strategies are needed to provide flexibility for their employees.

In this article, we will explore not just the concept of remote work, but also flexible work arrangements that can help create a more adaptable and supportive work environment suitable for all types of profession.

Member-only full article access available at APodA’s Human Resources Portal.

Special HR report | Part 2 | Do you know the latest on pay compliance?

This article delves into the complexities of pay compliance. It explores what it is, its importance, and the risks involved should employers be non-compliant; including hefty fines.

Pay compliance is a critical aspect of an employer’s role in the workplace, and includes a broad range of legislative obligations and regulations designed to protect both employees and employers. The Fair Work Act 2009 (FWA), along with various state and territory laws, set the foundation for these requirements, ensuring that employees receive fair wages and proper working conditions among other entitlements. Compliance with these laws is not just a legal requirement but also a vital component of maintaining a fair workplace.

Member-only full article access available at APodA’s Human Resources Portal.