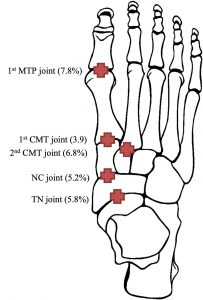

Foot osteoarthritis (OA) is a common cause of foot pain found in one in six people aged over 50 years. In fact, 69% of this group report disabling foot pain. The first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) is the most commonly affected joint in the foot (7.8%), followed by the midfoot joints, the second cuneiform-metatarsal (CMT) joint (6.8%), the talo-navicular (TN) joint (5.8%), navicular-first cuneiform (NC) joint (5.2%) and first cuneiform-metatarsal (CMT) joint (3.9%).

Two distinct types of OA

Two distinct phenotypes of foot OA are identified, being:

1. Isolated first MTPJ OA

2. Polyarticular foot OA (which is a more widespread form of OA that involves multiple midfoot joints). The polyarticular foot OA is associated with more pain and functional limitation compared with other classes.

As both first MTPJ and midfoot OA are common conditions seen by podiatrists, understanding the differences in its clinical presentations will assist in its diagnosis and help inform treatment decisions.

#1 First MTPJ OA

#1 First MTPJ OA

This is found more commonly in females, with increased age and lower socioeconomic classes. Structural factors associated with the condition include the following:

- A more pronated foot posture

- Longer distal phalanx

- Longer proximal phalanx

- Longer medial and lateral sesamoids

- Wider proximal phalanx

- Wider first metatarsal.

Common symptoms

These include pain and stiffness within the joint. Observations include a dorsal exostosis, swelling, erythema and IPJ hyperextension.

Clinical assessments used to diagnose this condition include pain on palpation, limited first MTPJ dorsiflexion (<64 degrees), crepitus and a hard-end feel.

Diagnosis

First MTPJ OA can be diagnosed either clinically or with radiographs.

Treatment

First line treatment options for foot OA generally include NSAIDs, foot orthoses, footwear modifications and intraarticular injections.1-4 If conservative measures fail, surgical options are considered.

The treatment options for first MTPJ OA have only been researched in a handful of randomised controlled studies. From these studies there is some evidence that sesamoid manipulation/mobilisation, flexor hallucis longus strengthening (isometric and isotonic contractions) and gait retraining (reinforcing the functional use of the hallux flexors) is more effective in the short term (four weeks) than conservative physical therapy treatments alone.

The use of arch contouring foot orthoses (full length prefabricated orthotic with individualised rearfoot varus wedging and a first MTPJ cut out and trimming the distal edge to the level of the second to fifth toe sulci) provided similar effectiveness to rocker-sole footwear (MBT®) for improving foot pain, function and quality of life at four, eight and 12 weeks. However, the risk of adverse events were lower in the foot orthoses group.

Carbon fibre shoe stiffening inserts have also been shown to be beneficial in improving pain compared with sham (soft) inserts at four and 12 weeks. Other treatments which have been researched include a single injection of Hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc®) which offered no benefit when compared to placebo for improving foot pain, function and quality of life.

When looking at the randomised controlled studies which examined surgical interventions for first MTPJ OA, one study found that an arthrodesis provided superior effectiveness to a total joint arthroplasty (ArCom® unconstrained joint toe replacement) for improving pain for end stage hallux rigidus. Another trial found a small synthetic cartilage bone implant (Cartiva®) provided equivalent effectiveness to arthrodesis for improving pain and function in advanced hallux rigidus, which could be an alternative procedure in patients who wished to maintain first MTPJ motion.

When looking at non randomised controlled studies, the evidence behind the treatment of first MTPJ OA suggest that people tend to respond well to conservative treatments. These studies found treatment options such as footwear education (wider toe box), foot orthoses and corticosteroids successfully reduced pain and returned patients to previous activity.

Treatment options I find useful for first MTPJ OA (hallux limitus pain) within the clinic include:

- Footwear education (wider toe box/rocker sole)

- Taping, physical therapy (foot/ankle mobilisations/dry needling)

- Custom orthotics with any modification to encourage first ray propulsion or decrease load through the forefoot (first MTPJ cut out/metatarsal dome).

- Increasing strength within the lower limb to increase the foot's capacity to withstand load. These include variations of calf raises, toe yoga (hallux/flexor hallucis brevis push downs while lifting lesser toes and vice versa) and proximal strengthening to the hip where required.

#2 Midfoot OA

Midfoot OA is more prevalent in individuals aged over 75 years, in women and those in routine occupations, and is associated with the following: obesity, pain in other weight bearing joints and previous foot and ankle injuries. Structural factors associated with midfoot OA include the following:

- A more pronated foot posture

- Greater first ray mobility

- Less range of motion in the subtalar and first metatarsophalangeal joints

- Longer central metatarsals

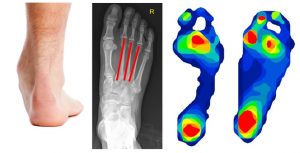

- Increased plantar pressures and contact times in the heel and midfoot during walking.

Control Midfoot OA

Common symptoms

These include the following: Tenderness across the midfoot that is made worse by passive pronation and abduction of the foot. Also, having a higher Arch Index score (indicating a more pronated foot posture) appears to be a useful predictor of symptomatic midfoot OA.

Diagnosis

Due to the complexity of the midfoot, it is inherently difficult to reliably measure the motion within these joints.

Although there are measures of midfoot mobility (variations of the navicular drop test), there are currently no valid clinical measures used to diagnose midfoot OA. Therefore, currently midfoot OA requires radiographs to confirm its diagnosis, as the current clinical assessments have either not been studied or are not strongly correlated with its diagnosis.

Treatment

The treatment options for midfoot OA have only been researched in one randomised control study, which compared functional custom foot orthoses with sham orthoses.

This study found significant biomechanical changes and greater improvement in pain and function at 12 weeks.

When looking at non randomised control studies, there is evidence which found NSAIDS, physical therapy, corticosteroids, foot orthoses, carbon fibre insoles and surgery beneficial in midfoot OA5-7. The surgical management of midfoot OA requires arthrodesis of the affected joints, however most cases are related to traumatic midfoot OA as a result of a Lisfranc injury, as opposed to non-traumatic degenerative midfoot OA.

Treatment options I find useful for midfoot OA within the clinic include footwear education (lacing techniques for the dorsal foot/encouraging less compression on the midfoot from tight footwear), custom orthotics designed to decrease the compressive forces in the midfoot and reduce plantar pressures in the heel and midfoot.

As there is some evidence that people with midfoot OA have more mobility within their first ray, similarly to first MTPJ OA, strengthening the lower limb and muscles that insert into the foot may help stabilise the joints within the foot.

In addition, people with midfoot OA have less range of motion in the first MTPJ and subtalar joint – so any treatments to encourage the mobility within these joints may be of benefit (foot/ankle mobilisation/dry needling/stretching/strengthening). However, future research is required to further our knowledge for the best treatment options for both first MTJP and midfoot OA, as currently the evidence is extremely limited.

In addition to clinical interventions, education and the language we use to educate patients on foot OA may have an impact on their clinical outcomes. Instead of using threatening words such as ‘chronic degenerative changes’, ‘bone on bone’ or ‘damage’, some alternatives and less threatening words include ‘normal age changes’, narrowing/tightness’ or ‘reparable harm’.

Summary

Foot OA is found in one in six people aged over 50. Multi-joint presentation is common, with two distinct phenotypes of either first MTPJ or polyarticular midfoot OA. Both are associated with an increase in age, female sex and lower occupational classes. First MTPJ OA has more clinical assessments to aid its diagnosis, compared with midfoot OA which is harder to diagnose clinically. Evidence-based treatment options are limited, however there is growing evidence behind anti-inflammatory modalities, foot orthoses, carbon fibre shoe stiffening inserts, footwear, physical therapy and surgery once conservative measures fail.